The sinking of the RMS Titanic on April 14, 1912, remains one of the most infamous maritime disasters in history. While it’s widely known that the ship struck an iceberg and sank, the full story reveals a tragic chain of miscommunication, human error, and environmental conditions—factors that could have prevented or at least lessened the disaster. But there may be more to the story than we’ve been told.

Some argue that this collision could have been avoided. Four days after departing Southampton, England, the Titanic struck an iceberg at 11:40 PM. Instead of a head-on collision, which might have resulted in less damage, the ship scraped along the side of the iceberg, rupturing five of its supposedly watertight compartments.

This breach doomed the vessel, leading to the deaths of 1,514 of the 2,224 passengers and crew onboard.

Just an hour before the collision, the nearby ship Californian radioed a warning about heavy ice. Because the message didn’t begin with “MSG” (Master Service Gram), Titanic's radio operator did not treat it as urgent and failed to inform the captain. That small oversight cost precious time.

One must also ask: why would an experienced radio operator ignore such a warning?

Another major issue was the lack of equipment. The ship’s lookouts in the crow’s nest, Frederick Fleet and Reginald Lee, didn’t have binoculars. Some reports suggest they were misplaced, while others claim they were locked away and the key had been taken off the ship before departure. Regardless, this is often blamed as a contributing factor. But here's something surprising: some experts believe that spotting an iceberg is actually easier with the naked eye. Binoculars can narrow your field of vision and limit peripheral awareness. In fact, without binoculars, the iceberg might have been spotted sooner—so that argument may not hold water. The sea was unusually calm that night, meaning visibility was generally good.

When the iceberg was finally seen, First Officer William Murdoch ordered “hard astarboard” and for the engines to reverse. However, this order was allegedly misunderstood by Quartermaster Robert Hichens, who initially turned the ship in the wrong direction. Though the mistake was quickly corrected, it wasn’t enough. The iceberg struck the side of the ship moments later.

The Titanic was equipped with only 20 lifeboats, meeting the legal minimum but not nearly enough for everyone onboard. Even worse, many of the lifeboats were launched half-full due to conflicting interpretations of the captain’s orders. Some officers believed the order "women and children first" meant women and children only, resulting in lifeboats departing with empty seats. It’s estimated that more than 400 additional people could have been saved if the lifeboats had been filled to capacity.

Some researchers have suggested that the Titanic’s steel hull and rivets were structurally weaker than they should have been. That may indicate that it may not have been a brand new ship. Material scientists have found high levels of slag in some of the rivets, which may have made them brittle and more likely to snap under pressure. While the shipbuilders denied that this contributed to the disaster, it’s possible that stronger materials could have slowed the rate at which the Titanic broke apart.

But what if we don’t know the whole truth about the Titanic? What if there was much more to the story than we’ve been told? Long after the fact, rumors began to circulate—rumors that evolved into full-blown conspiracy theories with enough circumstantial evidence to raise eyebrows.

The Switch Theory

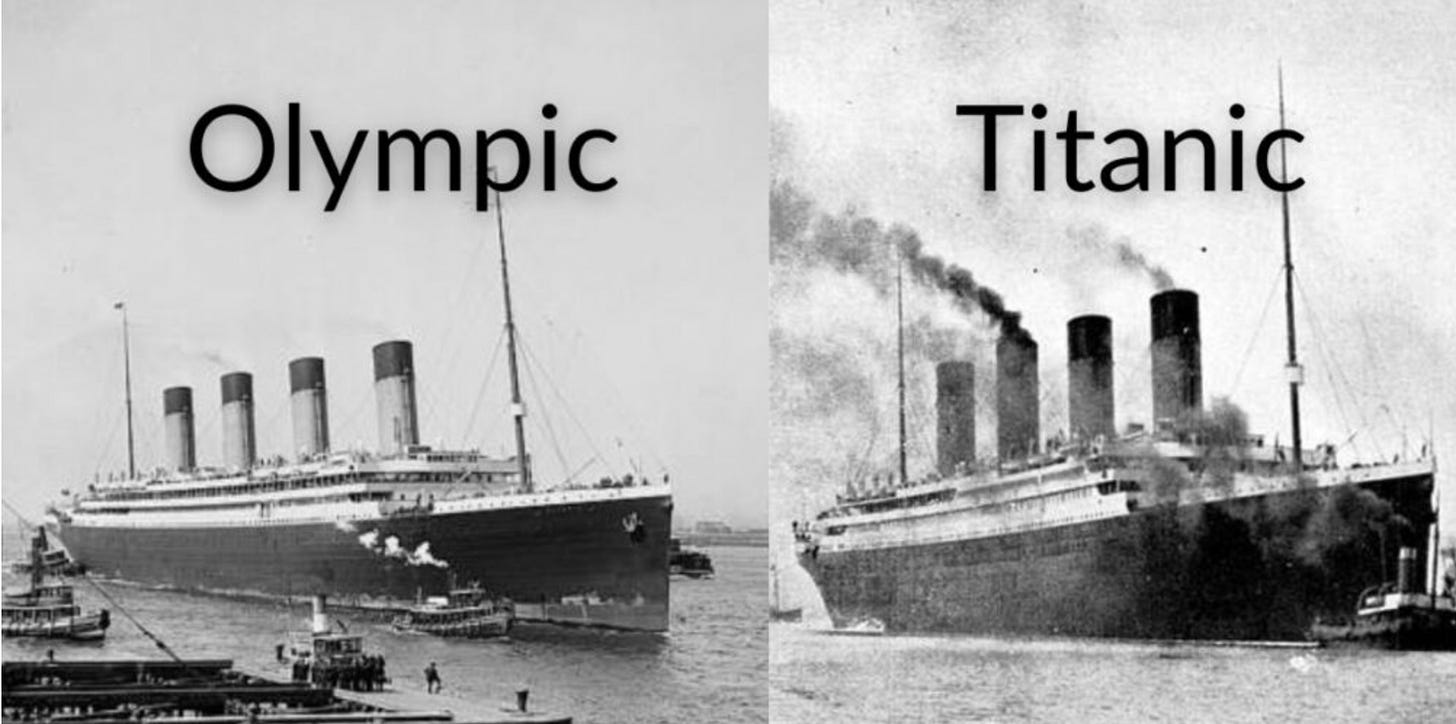

One of the most persistent claims is that the Titanic didn’t actually sink at all. Instead, her nearly identical sister ship, the Olympic, was deliberately sent to sea in her place and sunk as part of an elaborate insurance scam. Both ships were part of a trio of luxury ocean liners built by Harland & Wolff for the White Star Line. The Olympic launched first in 1910 and entered service in 1911. But shortly after, she collided with the Royal Navy warship HMS Hawke and suffered serious damage. According to some theorists, the Olympic was never fully seaworthy again and became a financial burden.

The theory suggests that, facing major losses, the White Star Line decided to switch the two ships. The damaged Olympicwas disguised as the Titanic, then sent out on a doomed voyage that would generate a massive insurance payout. Meanwhile, the real Titanic was quietly renamed Olympic and remained in service until 1935. The Titanic was insured for more than the Olympic, and the company allegedly stood to profit from the loss.

Supporters of this theory point to inconsistencies in the number and placement of portholes, claims that the Titanic appeared unusually worn at her launch, and reports that some experienced crew members refused to board the ship. But critics argue that switching two 46,000-ton ships in secret would have required enormous logistical coordination. Paperwork could be forged, yes, but convincing the hundreds of workers and crew involved would have been much more difficult. Furthermore, official shipyard records, service logs, and final dismantling reports of the Olympic contain no indication that such a swap occurred. When the Olympic was scrapped in the 1930s, no evidence emerged to suggest she had once been the Titanic.

Another conspiracy theory centers around the powerful American financier J.P. Morgan. According to this idea, Morgan orchestrated the disaster in order to eliminate three influential men—John Jacob Astor IV, Benjamin Guggenheim, and Isidor Straus—who allegedly opposed the formation of the U.S. Federal Reserve. At the time, the American banking system was disorganized and unstable, and Morgan was among the key figures pushing for the creation of a centralized authority.

Astor, Guggenheim, and Straus were all passengers on the Titanic. All three died. J.P. Morgan himself had booked a luxurious first-class suite on the ship but canceled at the last minute, citing illness. He was later photographed in good health, relaxing in France. The timing of his cancellation, paired with the deaths of these wealthy and powerful men, fueled suspicion. The Federal Reserve Act was passed the following year, in 1913, prompting some to believe that eliminating key opponents made the path easier for Morgan and his allies.

While intriguing, this theory has its weaknesses.

There is no documented evidence that Astor, Guggenheim, or Straus were publicly opposed to the Federal Reserve. The claim is mostly based on hearsay. And while the survival of certain passengers raises eyebrows, the disaster’s chaos made outcomes unpredictable. Many influential people died, but others survived. If this was an assassination plot, it was a remarkably risky and imprecise one.

In the end, we may never fully know what happened aboard the Titanic that fateful night. It was a tragedy shaped by human error, poor planning, and environmental conditions—but perhaps also by motives still hidden from public view. As long as unanswered questions linger, the search for the real story behind the Titanic will continue.